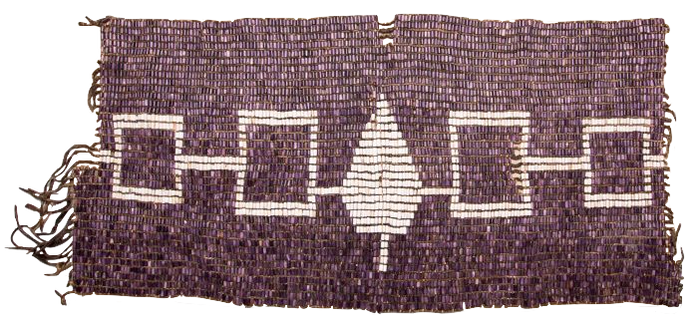

Wampum beads were arranged and strung together in intricate patterns and designs that typically served as a visual memory keeper recording important messages, agreements, and historical events. These beautiful creations came to be known as wampum belts in English, though they typically were not worn in the same way we think of belts today. The use of wampum belts used to be thought of as something belonging only to the Haudenosaunee and Wampanoag people, but historians now believe it was far more widespread that previously thought. There is now evidence of a wampum tradition amongst the Ojibway, Odawa and Potawatomi people. Examples of wampum belts Arguably the most famous wampum belt is the Hiawatha belt made to tell the story of the creation of the Haudenosaunee nation (also known as the Iroquois Confederacy or just the five nations). The Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, and Mohawk people warred for a very long time. When they decided to join together in peace, the Hiawatha wampum belt was created to record the event. The box on the far left stands for the Mohawk who were the first to join, then the Oneida. The central figure is a white pine, the tree of peace, where the warring nations buried their weapons. It symbolizes the Onondaga. Next is the Cayuga, and then the Seneca. Note that they are all joined together. This was a reminder to maintain the peace. The Wolf Treaty belt represents the alliance of the Seven Nations (an alliance of seven Native communities in what is now Canada) and the English. The figures in the center represent King George I and a Native person joining hands in peace. The wolves were there to protect the peace path. Note the seven dark lines by each wolf. These purple lines represented the Seven Nations. In 1890, this was written about the belt: "One wampum, now owned by Margaret Cook, the aged aunt of Running Deer, represents the treaty of George I with the Seven Nations. The king and the head chief are represented with joined hands, while on each side is a dog, watchful of danger, and the emblem is supposed to be the pledge: 'We will live together or die together. We promise this as long as water runs, skies do shine, and night brings rest.'" You can find photos and stories of more wampum belts at the Onondaga Nation website: https://www.onondaganation.org/culture/wampum/ Anishinabek Nation. “What Are Wampum Belts?” YouTube, 23 June 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=95PojatWRdc.

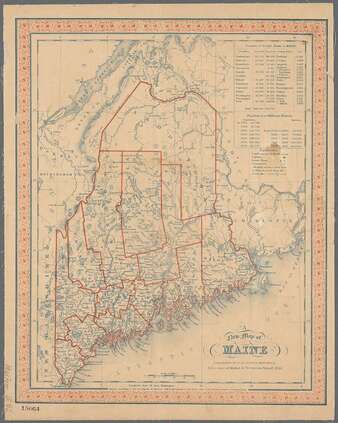

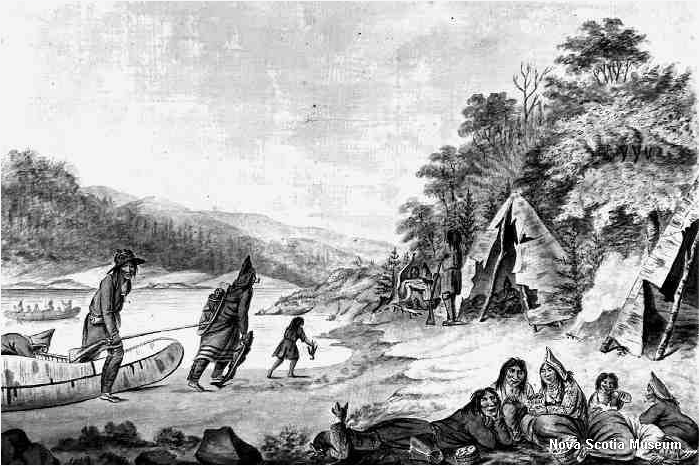

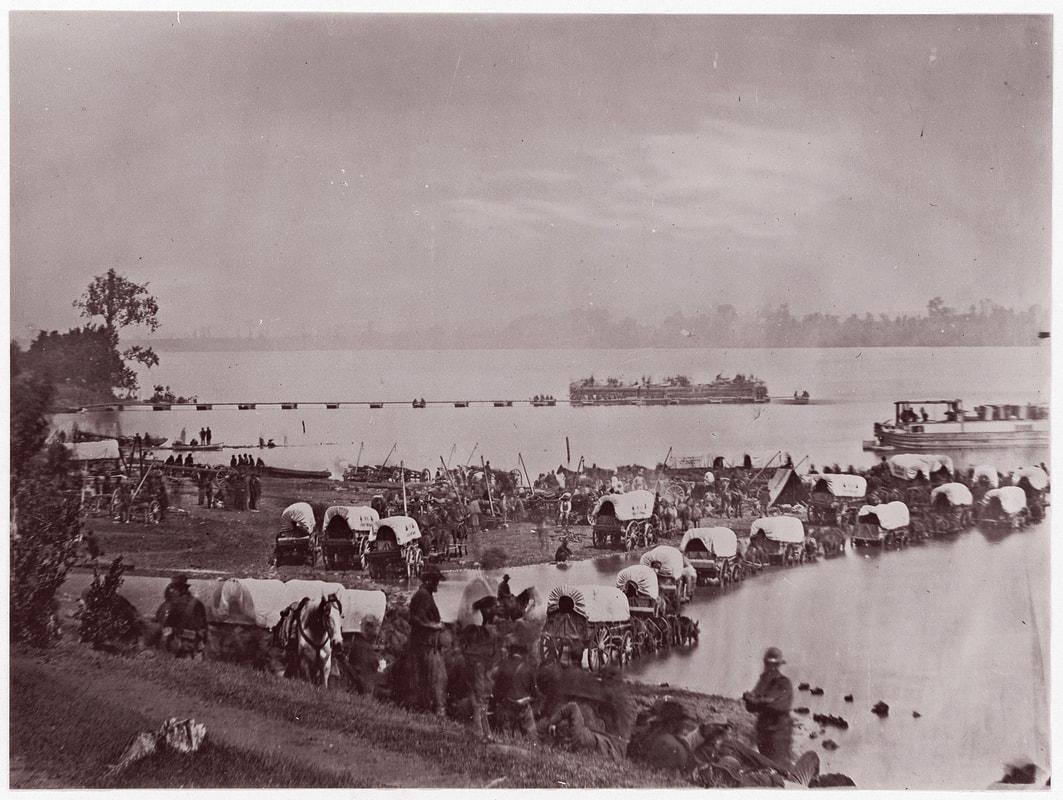

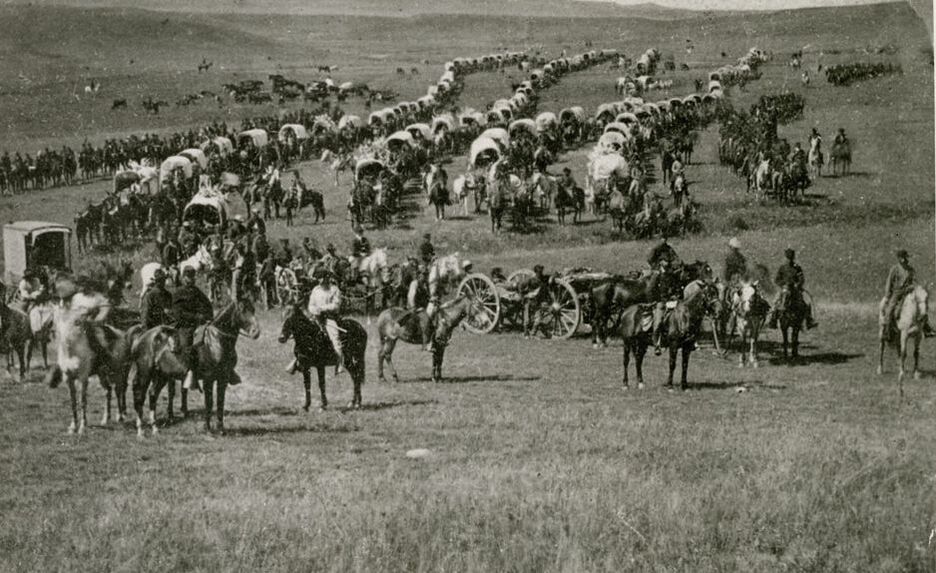

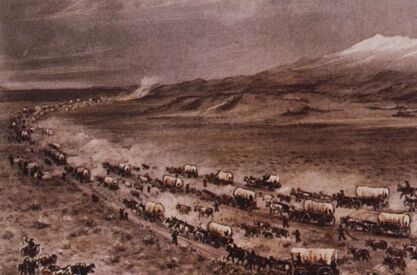

Bonaparte, Darren. The Wolf Belt. http://www.wampumchronicles.com/wolfbelt.html. Accessed 29 Mar. 2024 “Hiawatha Belt.” Onondaga Nation, 18 June 2014, https://www.onondaganation.org/culture/wampum/hiawatha-belt/. Historica Canada. “Richard Hill.” YouTube, 2 June 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8Ckxi7rjGac&t=717s. Nahwegahbow Windspeaker, Barb. “Wampum Holds Power of Earliest Agreements.” Ammsa.Com, 2014, https://web.archive.org/web/20190228192256/https://ammsa.com/publications/windspeaker/wampum-holds-power-earliest-agreements#sthash.Bv7JG8PF.dpuf. “Wampum.” Onondaga Nation, 18 Feb. 2014, https://www.onondaganation.org/culture/wampum/. “Wampum Belt.” Plimoth Patuxet Museums, 30 Aug. 2023, https://plimoth.org/yath/unit-2/wampum-belt. The contents of this article are summarized from a Cowasuck.org webpost that is no longer active. Some changes have been made to simplify or clarify language for young readers. Additional information regarding the role of women was added with the source listed below.  Wikimedia Commons Wikimedia Commons The division of jobs was based on a philosophy of life, a religious belief. In general, the men hunted for wild game and gathered fish. The women worked in the fields. It is often assumed by many commentators that the life of the Native man was one of leisure, with the bulk of the heavy work done by the woman. The man was responsible for hunting, trapping, fishing, clearing trees, building the wigwam or long house, making the canoe, carving the household cooking and eating items, and instructing the young boys. Perhaps most importantly, he was also responsible for ensuring the safety of his family, clan, and band. The women gathered water and wood. They prepared and cooked meals, picked all types of berries and nuts. They gathered lily roots, wild rice, onions, chives, wild garlic, mushrooms, mint, swamp cabbage among many of the wild plants. They gathered herbs for medicines and garnishes. Additionally, women cared for, raised, and educated the children. They tended to births and deaths. They prepared hides, made clothes and snowshoes, set up and tore down shelters, and after engaging in all these physical tasks, women were also the primary decision makers. Women were involved in all major decisions involving their community. [Girouard, 2017] The women also planted the "three sisters" crops. On a big mound, they planted corn that grew upwards and provided natural poles for beans. Then squash or pumpkins were planted at the base where they spread all around the mound providing a cover to keep in the moisture and prevent weeds. All three were harvested at the same time. They were also dried to be used during the winter. There could be no sustenance farming of the "three sisters" if there existed danger of enemy raids against the villages. Therefore, defense was an important aspect. In the historic period, it became necessary to erect perimeters of palisades around the village. Men were responsible for cutting down long trees, most likely pine, which were then sharpened on both ends and embedded several feet into the earth around the main village dwellings. Look-out towers stood high above, so that there would be a chance of early warning should danger threaten. To be a warrior meant that one had to endure without complaint cold, hunger, pain, and weariness. This was what the young boys aspired to, and with the help of their maternal uncles, they were trained from an early age to shoot the longbow and wield the tomahawk and knife. They learned to walk swiftly and silently through the forest, tracking animals or people with deadly skill. Girouard, M. (2017, March 15). Wabanaki women - blog for Women’s History Month. Wabanaki REACH. https://www.wabanakireach.org/wabanaki_women_blog_for_women_s_history_month  Wikimedia Commons Wikimedia Commons During the American Revolution, Germany was made up of more than 300 small regions. These regions supplied soldiers to the British to fight against America. The largest group came from Hesse-Cassel. Because of this, all the German soldiers fighting with the British were called Hessians. King George III of Britain paid for the services of the Hessians because he didn't have enough soldiers for his army in America. The German soldiers, although often thought of as mercenaries, didn't get much in return for their service. Most of them only received basic necessities. The Prince of Hesse-Cassel, Frederick II, made a good deal by selling the services of 12,000 Hessians to the English. In total, around 30,000 German soldiers fought for the British in North America. When they arrived, they found a large German-American community of almost 200,000 people. Many Hessians were tempted to desert the British and stay in this new land with its growing German population, so about 5,000 Germans chose to remain in America, while the rest went back home. This is a small excerpt of an article originally posted on the Penobscot Marine Museum website, which is no longer posted. It has been edited slightly with simplified vocabulary for young readers.  Between 1675 and 1763 there was a nearly continuous series of wars in Maine between the British and the French/ Indians (the term at the time for the Native People and the origin of the name "French and Indian Wars"). Both groups wanted Maine’s land and resources. The wars were related to conflicts in Europe at the same time. In King Philip's War (1675-78), the English fought the French and Native People for Castine. During King William's War (1688-99), the French and English fought over Acadia—included Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and much of Maine. The treaty ending this war resulted in the Natives deeding more land to the English. It caused a long-lasting misunderstanding between the Native and non-Native people. Queen Anne's War (1703-1713) : In 1713 the Treaty of Utrecht between France and England gave all of Acadia to English. This caused more disputes between the English and the Native People over land. The French still held Quebec. More wars resulted over the next 50 years: Dummer's War (1722-1727), King George's War (1744-1751), and the French and Indian War (1754-1763). These years were devastating to settlers and Native People alike. From 1689 to 1713, not a single English home stood in Maine north of Wells. English treatment of the Native People worsened the situation. They forced tribal leaders to sign land deeds that were misunderstood. The French encouraged the Native People to attack English settlers. English retaliation against the Natives included bounties on scalps. The French encouraged Maine’s Native People to form the Wabanaki Confederation, making the English even more worried about protecting their settlements in Maine. The English captured French Quebec in 1759, which led to the signing of the Treaty of Paris ending the French and Indian Wars. It also ended the French presence on the Maine coast, resulting in slow, but increased settlement of midcoast and downeast Maine after 1760. All of Canada was given to England. The British issued a proclamation promising Native People the right to keep all the lands they held at the end of the war. Bad feelings between the English and the Native People still existed, however, because the English continued to gradually move into and take over Native lands for farming and hunting. Throughout these wars, Europeans on the coast of Maine created sparse but determined settlements of fishermen, traders, and lumbermen who paid little attention to official developments and proclamations of the English and French nobility. These small settlements of Scotch-Irish fishermen and farmers were the origins of Maritime Maine. The following are actual quotes from people traveling the Oregon or California Trails. They appear exactly how they were written. Education was not as common in those days and spelling was not standard, so some words may be misspelled or the grammar may be incorrect.

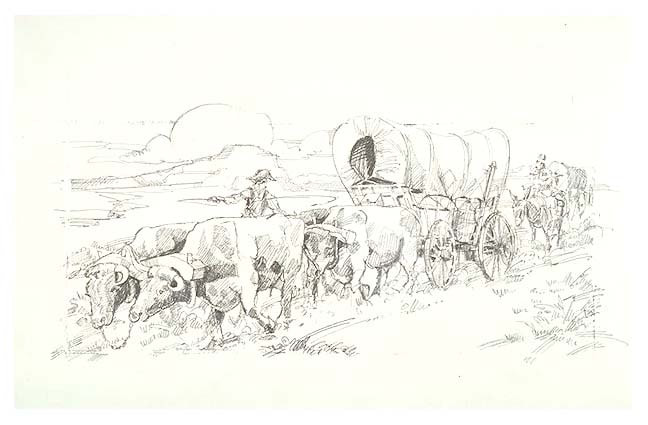

Mary Jane Smith, 1852 May 23rd: Today we had our first death, that of a small child from whooping cough. Bad Camp. Poor grass and no wood. May 23rd: Today a division of opinion arose, some wanted to stay here, others to go on to a better place to camp so 6 wagons left including Hunt, Watkins, Craig, and Stroup who get out by themselves. June 26th: This morning we overtook Mr. Hunt. He was by himself having been left by his company near Laramie. One of his children, Mr. Craig's wife, Mr. Watkins and a young man named Jones and a young man named Garrett had all died of Cholera. Garrett seems to have been traveling west with the Hunts. Margaret A. Frink, 1850 Monday, July 8: It rained considerably during the night. Mr. Frink was on guard until two o’ clock, when he returned to camp bringing the startling news, that for some unknown cause, the horses had stampeded. We had no means of knowing whether it was the work of Indians or not, but it was useless to look for them in the darkness… (the animals were found the next morning) When we arose, we found the range of mountains covered in new-fallen snow. This is a beautiful valley, and when under settlement and cultivation, will be a delightful region… At half past ten we passed a village of Snake River Indians (Shoshone).

J.T. Kerns, 1852

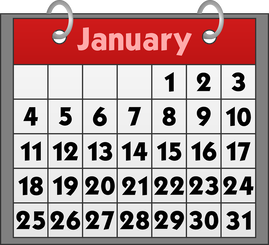

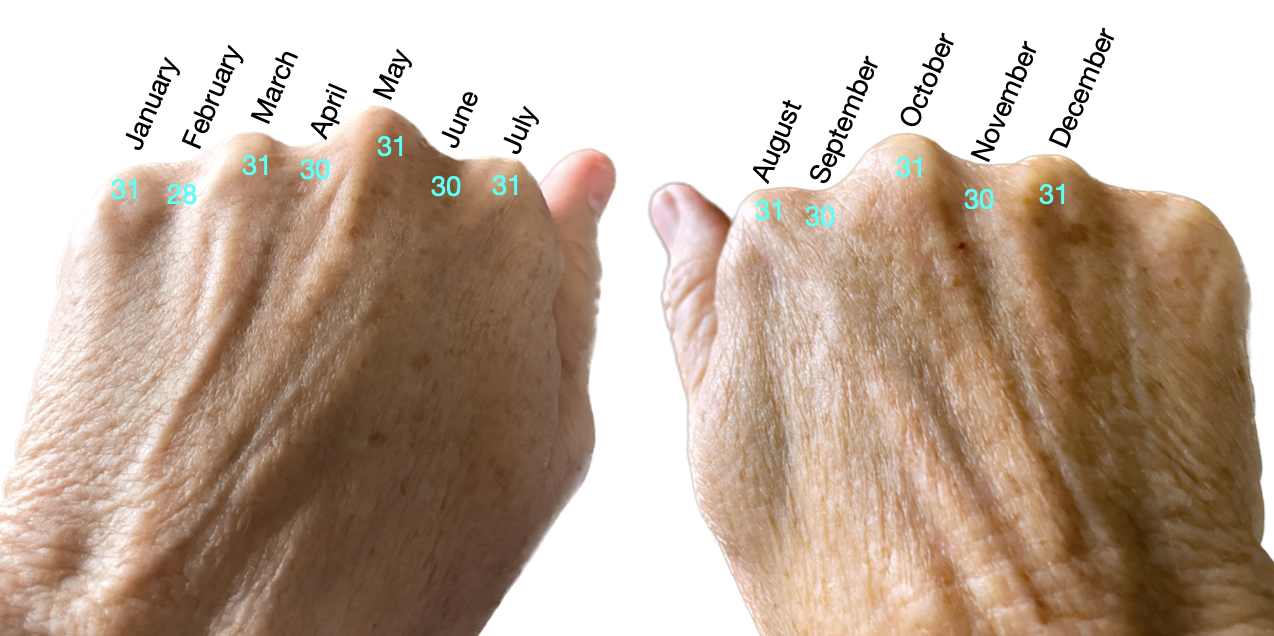

July 18 Traveled up Thomas’ fork of the Bear river, twelve miles to the ford and encamped on the west bank. Country nice and streams full of fish. Some good farms might be made along here, as the valleys are rich and the mountains high enough to preserve an eveness of temperature and supply of sufficiency of timber. July 19 This day drove 25 miles over a mountainous, picturesque country, possessed of rich valleys, beautiful springs, and streams abounding with fish. Timber is, however, scarce for to supply the demands of a farmer. Medorem Crawford, 1842 May 16 Left camp at 1 o'clock E. drove 15 mi. and camped at 7 o'c. E. on the Sanafe rout, found water pleanty, wood & pasture scarce. In our company were 16 waggons & 105 persons including children & men over 18 years of age. May 21 Mrs. Lancaster's only child a daughter 16 months old died 10 o'clock M the Doctor called the disease symptomatick fever accompanied with worms." After burying child we started and drove 6 miles. Memory Tricks Mnemonic—pronounced ni-mon-ik, the ‘M’ is silent—are memory devices or strategies to help you remember information. Below are some examples. Creating your own “memory tricks” will come in handy in a variety of situations (e.g., tests, trivia bowls, spelling, remembering lists). Everyone processes information differently so when formulating mnemonics, get creative and determine what works best for you. Rhyming or poetry mnemonics  A mnemonic for remembering how many days are in each month: Thirty days hath September April, June and November. All the rest have thirty-one, But February, it is great And brings to us twenty-eight, Unless it steps out of line And brings to us twenty-nine (leap year occurs every four years) “When two vowels go walking, the first one does the talking.” This means that when there are two vowels in a row, the first usually has a long sound and the second is silent. That's why it's team, not taem; coat, not caot; and wait, not wiat. Remembering this rule will help you to put vowels in the right order. The popular cheer "'S' 'U' 'C' 'C' 'E' 'S' 'S' that's the way we spell success." Acronyms as mnemonics An acronym is a word or phrase that is made from the first letter of each word or phrase you are trying to remember. RICE is a mnemonic for treating a sprain: Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation. HOMES is a mnemonic for the five Great Lakes—Huron, Ontario, Michigan, Erie, and Superior. ROY G. BIV is a mnemonic for the seven colors of the rainbow—Red, Orange, Yellow, Green, Blue, Indigo, and Violet. A mnemonic for remembering the order of the planets is: My Very Excellent Memory Just Summed Up Nine Planets (this was used before Pluto was downgraded to no longer being a planet) Mnemonics for spelling Desert vs. Dessert Desert is the hot, dry place where cacti grow. Dessert is the sweet treat you have at the end of a meal. You may want more than one dessert and it has more than one s. That will help you remember how to spell it. Foul vs. Fowl It may be helpful to remember that the word fowl—birds raised with the intent to be used as food—contains the word ‘owl’. Since an owl is a bird and since the word fowl contains the word owl, associating it in this way may help you remember to write the word fowl and not foul when referring to birds. Principal vs. Principle To distinguish principle from principal think of "the principal is your pal." Hear vs. Here When you remove the ‘h’ in hear you are left with the word ear. As you know, your ear is what allows you to hear. You hear with your ear. Made vs. Maid When you remove the ‘m’ in maid you are left with the word aid. Think of your maid as your aid, someone who helps you cook, clean, etc. Heal vs. Heel When you remove the ‘thy’ in healthy you have the word heal. Since heal means to regenerate healthy tissue, it may be helpful to associate the word healthy with heal. Heel (the bottom back part of the foot). Heel contains two consecutive vowels of the same letter ‘e’ and ‘e’. (Heal does not.) Foot also contains two consecutive vowels of the same letter, ‘o’ and ‘o’. It may help you to remember this so that you always associate the word heel with foot. Other mnemonics

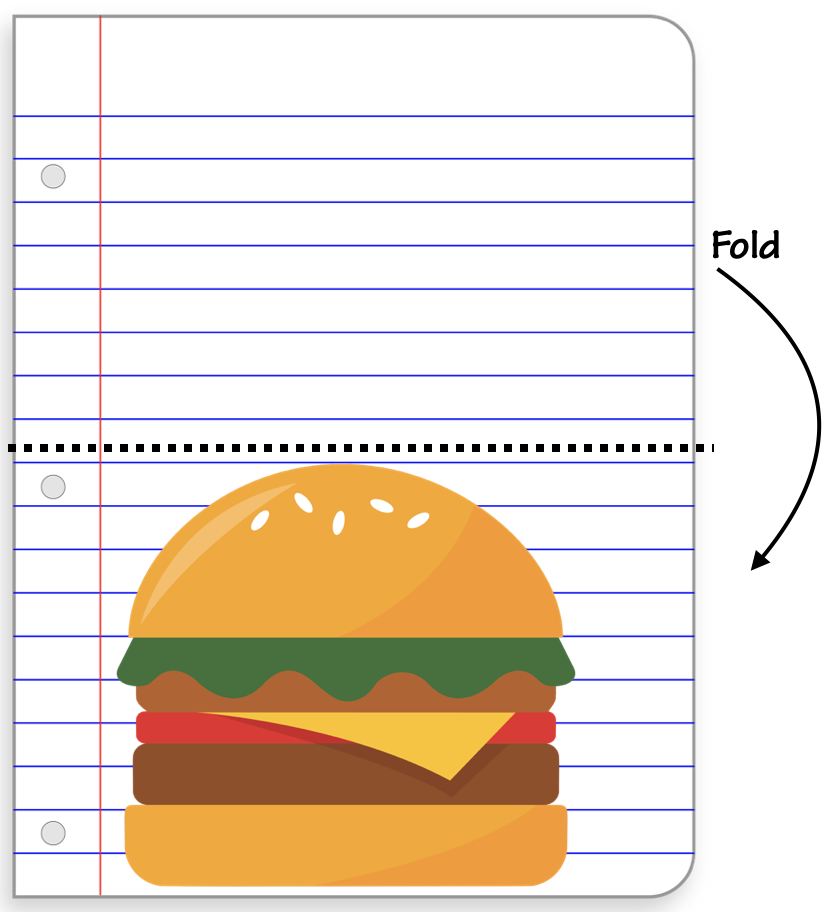

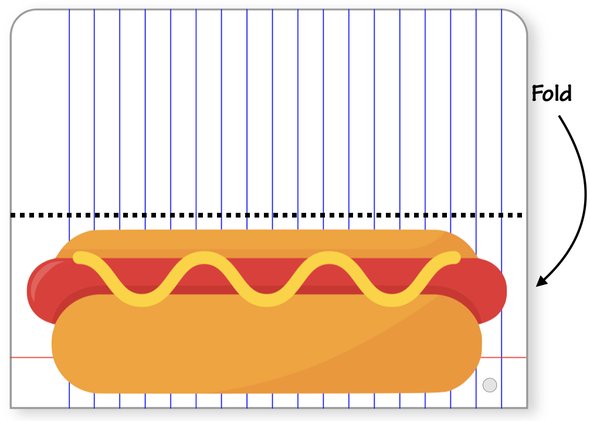

hotdog fold

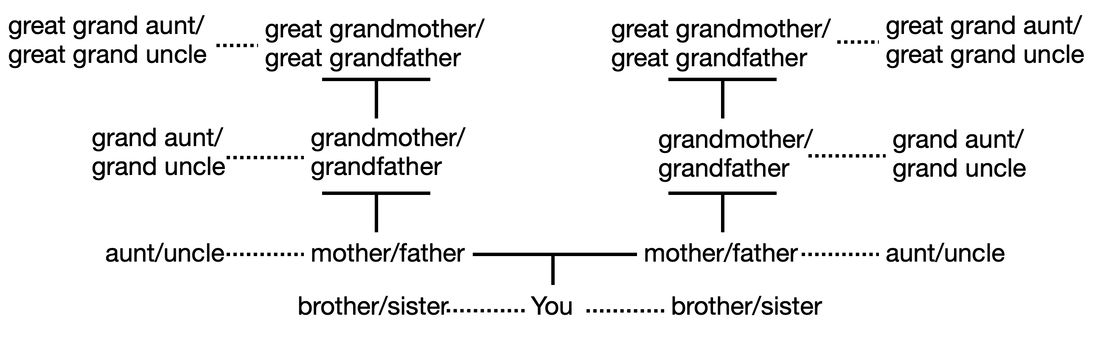

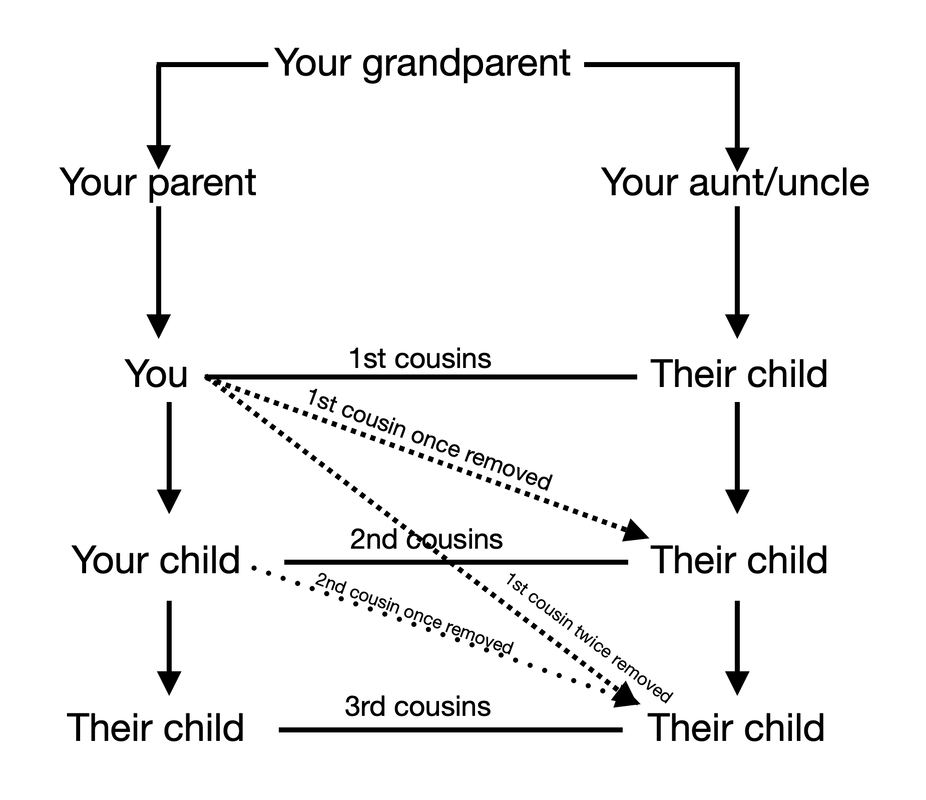

The parents of your father and/or mother are your grandparents (your grandmother and/or grandfather) and their parents are your great grandparents. Your parents' brothers and sisters are your uncles and aunts. The brothers and sisters of your grandparents are often called your great uncles or great aunts, but this is incorrect. They are actually your grand aunts and grand uncles. The brothers and sisters of your great grandparents are your great grand uncles and great grand aunts. What about the cousins? You may have heard some cousins referred to as your 1st cousin, or 2nd cousin. You may have even heard of them referred to as your 2nd cousin once removed. These relationships aren't as difficult to figure out as it seems.

Winning the right to vote

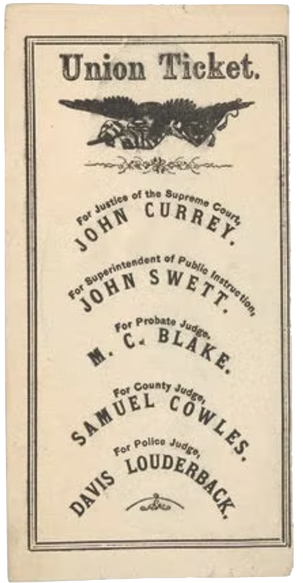

Voting rights of the 1960s In 1957 and 1960, laws were passed by Congress to safeguard African American voters. Despite this, during the 1964 presidential elections, they still faced difficulties in registering to vote, encountering opposition and even brutal violence during voter registration drives. In March 1965, Martin Luther King Jr. organized a march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, to draw attention to the issue. Following this, President Lyndon B. Johnson sent a voting rights bill to Congress, which was passed and became the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The Act empowered the U.S. attorney general to dispatch federal examiners to assist with African American voter registration and abolished literacy tests in certain states. It had an immediate effect, with around 250,000 new African American voters registered by the end of 1965. The Act was subsequently strengthened in 1970, 1975, and 1982, and was extended for 25 years in 2006 by President George W. Bush. However, in 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court invalidated a crucial provision of the Act in the Shelby County v. Holder case. The Court determined that states with a history of voter bias no longer required federal pre-approval to amend their election laws, affecting mainly Southern states. Chief Justice John Roberts cited improvements in voting conditions in these states as the reason for the Court's decision. President Barack Obama criticized the ruling, calling for new legislation to safeguard equal access to the polls for all voters. Mnemonics (the first m is silent) are tricks or strategies to help you remember information. A mnemonic can be a word, phrase, a rhyme, a song, or anything else you use to help you remember something. One mnemonic you know already is the alphabet song. This help kids remember the letters of the alphabet. Below are some other examples: HOMES Knowing the mnemonic H.O.M.E.S. can help you remember the names of the Great Lakes: Huron, Ontario, Michigan, Eerie, and Superior. This mnemonic uses the first letter of each lake to create another common word. spring forward, fall back knuckle mnemonic This mnemonic uses your knuckles to remember which months have 30 days and which have 31 (or 28). The higher bumps of your knuckles let you know a higher number should match, while the dips between your knuckles are lower, helping you remember a lower number corresponds with the dips. Dessert vs desert

|

Author

I often struggle to find websites with thorough explanations in simple language to help kids understand historical events or scientific concepts, so I decided to create some of my own! -Cookie Davis

Archives

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed