|

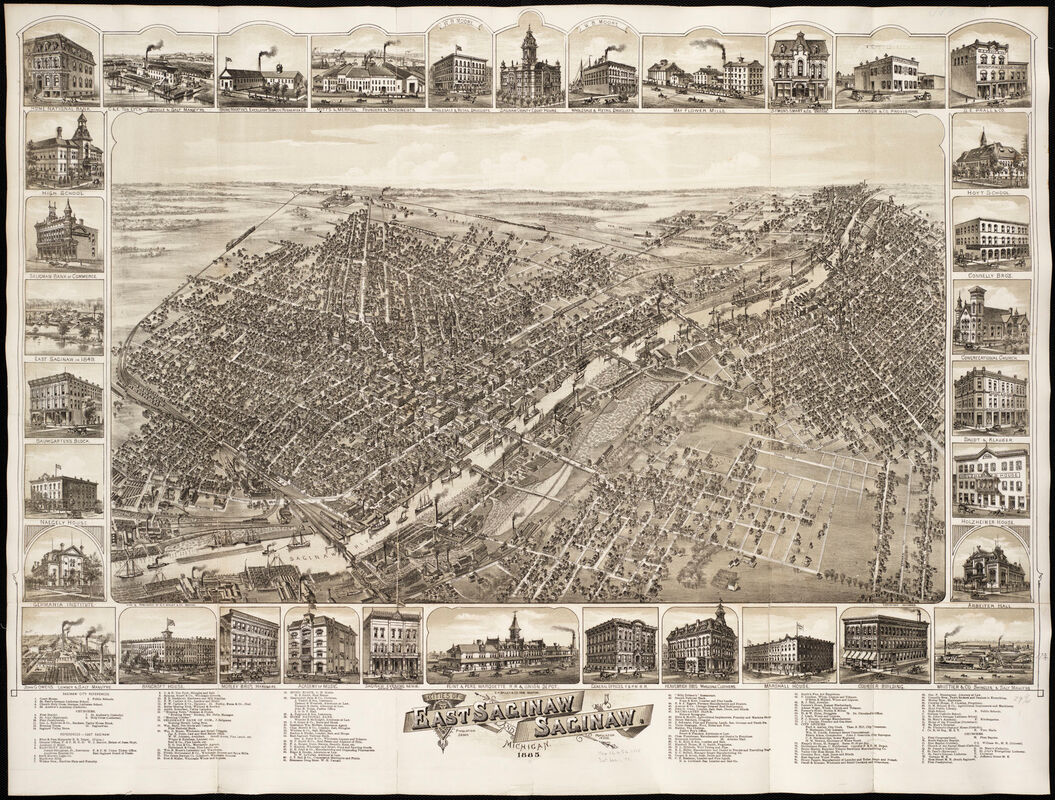

This article, which is no longer published, originally appeared on the site michiganrailroads.com. Some vocabulary has been simplified for young readers and images have been added to increase visual appeal. Saginaw was founded in 1816 as a trading post on the Saginaw River. The original town was planned in 1823 on the west side of the river. East Saginaw was founded in 1850, incorporated as a village in 1855 and a city in 1857. The entire Saginaw area was well known as the logging capital of east Michigan in the second half of the 1800s. East Saginaw was combined with South Saginaw in 1873 and with Saginaw City on the west side of river in 1889. The view above was from 1885.

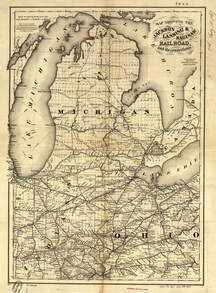

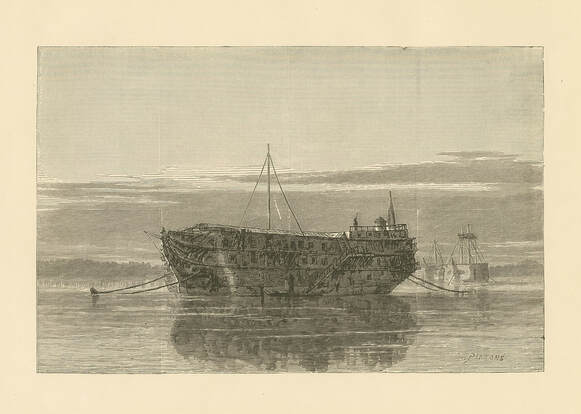

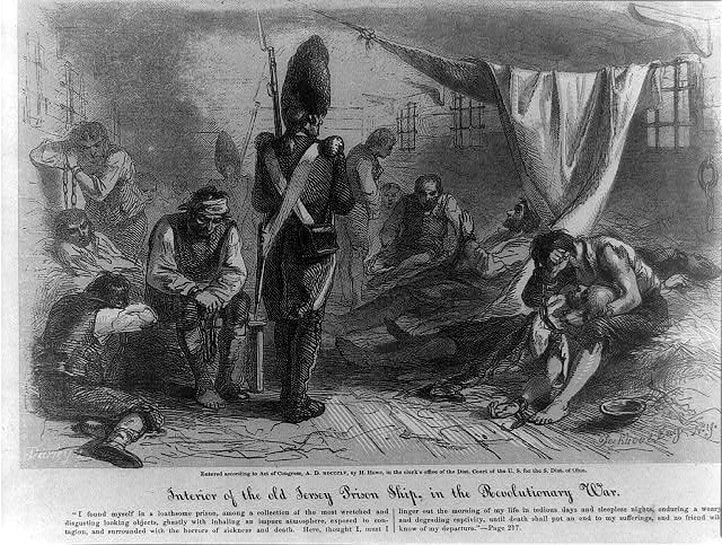

The Pere Marquette line west towards Alma was built in 1872, and a connection was built from the Detroit and Bay City Railroad from Denmark Jct. about 1873. Narrow gauge lines to Vassar and Reese were built in 1874 and 1882 respectively and converted to standard gauge later. In 1890, the predecessor to the Grand Trunk Western arrived from Durand and was built through east and west Saginaw to Bay City. Berry, Dale. “Station: Saginaw Michigan.” Michiganrailroad.com, www.michiganrailroads.com/RRHX/Stations/CountyStations/SaginawStations/SaginawArea/SaginawMI.htm. “Cities of East Saginaw and Saginaw, Michigan, 1885.” Wikimedia Commons, Wikimedia Foundation, 10 July 2008, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cities_of_East_Saginaw_and_Saginaw,_Michigan,_1885_(2675801518).jpg. G.W. & C. Colton & Co. “Map Showing the Jackson, Lansing & Saginaw Railroad and Its Connections.” Wikimedia Commons, Library of Congress, 30 May 2018, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Map_showing_the_Jackson,_Lansing_%26_Saginaw_Railroad_and_its_connections._LOC_98688688.tif. This is an excerpt from an article originally appeared on the website easyrivernyc.org that is no longer published. Images have been added to increase visual appeal and text simplified for students. More Americans died in British prison ships in New York Harbor than in all the battles of the Revolutionary War. There were at least 16 of these floating prisons anchored in Wallabout Bay on the East River for most of the war, and they were known for their filth, pests, infectious disease and horror. The ships were all wretched, but the most notorious was the Jersey. Following the Battle of Long Island in August, 1776, and the fall of New York City soon after, the British found thousands of prisoners on their hands, and the available prisons in New York filled up quickly. Then, as the British began seizing hundreds of seamen off privateers, they turned a series of aging vessels into prison ships. There were more than a thousand men at a time packed onto the Jersey. They died with such regularity that when their British jailers opened the hatches in the morning, their first greeting to the men below was: "Rebels, turn out your dead!" There were 4,435 battle deaths during the Revolutionary War, according to the Department of Defense. One historian estimated that there were between 7,000 and 8,000 prison ship deaths, but other sources claim even more. A letter-writer from Fishkill in 1783 claimed that on the Jersey alone, 11,644 died. Although that figure is unlikely for the one ship, it is reasonable for all the prison ships together, and is cited regularly. Built in 1735 as a 64-gun ship, the Jersey was was converted to a prison ship in the winter of 1779-1780. Virtually stripped except for a flagstaff and a derrick for taking in supplies, the Jersey was floated, rudderless, in Wallabout Bay, about 100 yards offshore of what is now the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Its portholes were closed and replaced by a series of small holes, 20 inches square, crossed by two bars of iron. There were various ways to get off the prison ships. The British had a standing offer that any prisoner could be released immediately if he joined the British forces, and an unidentified number did so. Prisoners who carried money with them could buy their way off the ship. Others managed to escape. Also, prisoner exchanges were quite common, with officers exchanged for officers, seamen for seamen, soldiers for soldiers. But for vast numbers of prisoners, there were only two possibilities: death or the end of the war, whichever came first. At war's end, survivors were released, and the prison ships abandoned. In later years, bleached bones of the dead were constantly exposed to the tides and weather along the Long Island shore. And well into the next century, low tide regularly exposed the rotting timbers of the Jersey, the ship they called Hell. Bookhout, Edward. “Interior HMS Jersey.” Wikimedia Commons, Wikimedia Foundation, 12 Nov. 2012, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki

/File:Interior_HMS_Jersey_1855.jpg. Daugherty, Greg. “The Appalling Way the British Tried to Recruit Americans Away from Revolt.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 31 Jan. 2020, www.history.com/news/british-prison-ships-american-revolution-hms-jersey. History.com Editors. “The HMS Jersey.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 19 Mar. 2010, www.history.com/topics/american-revolution/the-hms-jersey. “History: Tragedy: Prison Ships & General Slocum.” East River NYC, 2008, www.eastrivernyc.org/content/history/tragedy/index.html. “Prison Ship Jersey.” Wikimedia Commons, New York Public Library, 13 May 2016, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki /File:Prison_ship_Jersey_(NYPL_b13512824-420924).jpg. Light travels at different speeds through different materials, such as air, water, and glass. It travels more slowly through water and glass than it does through air. When light slows down or speeds up, it bends in a new direction. This bending of light is called refraction. Try these experiments

The Battle of Long Island, also called the Battle of Brooklyn, was an important battle for America's independence. The largest and deadliest battle of the Revolutionary War was fought in the New York City borough of Brooklyn. A large British fighting force, commanded by brothers General Howe and Admiral Howe gathered together in Brooklyn to meet George Washington and the Continental Army in the first major battle of organized forces in the Revolutionary War on August 27th, 1776.

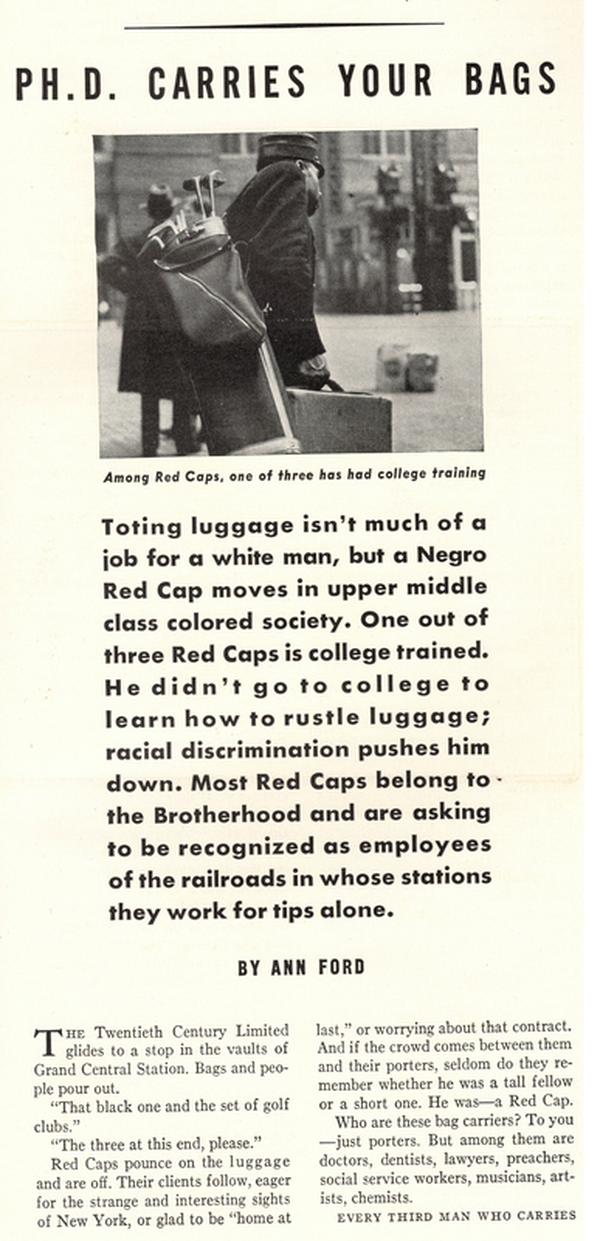

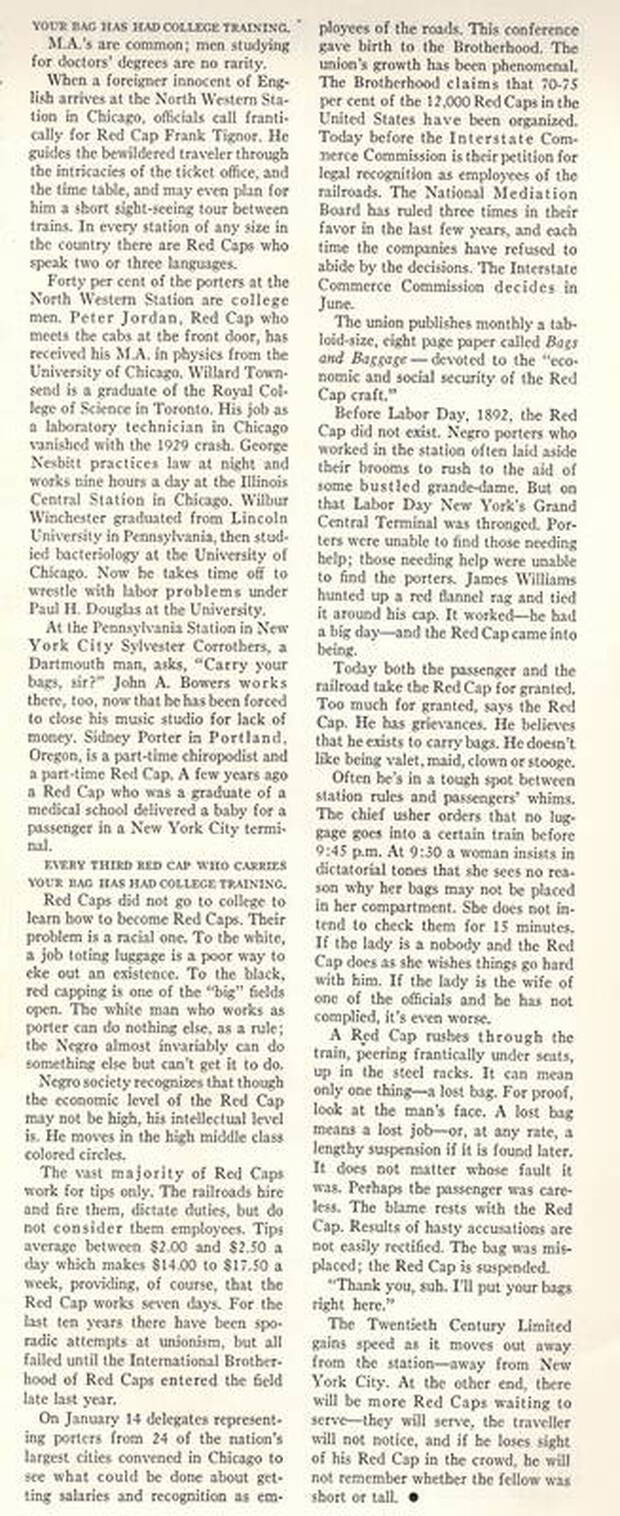

Both armies recognized the strategic importance of Manhattan Island (New York City) and the control of the Hudson River. Though young American army was driven to retreat and gave up Brooklyn and later Manhattan, the fact that they faced such a large and well-trained enemy, and survived only losing a fraction of their force was a victory in itself.  Wikimedia Commons Wikimedia Commons Despite their battle win, the British held back and this allowed Washington to take advantage of a rain-filled night to cover the sounds of moving almost his entire army across the river to safety. When the morning sun began to rise and some of the American troops were still on the island, luck was on their side as a dense fog moved in hiding their movement and enabling all of Washington's army to escape. The British plan of crushing the rebellion and quickly ending an "expensive war" was lost. It would be a harder fight than they realized. The Americans lost over 1,000 soldiers in the battle and were badly discouraged by the loss. However, they stood together as an army defending the nation, gained valuable experience, and eventually won the war. By the numbers, this battle was supposed to be a decisive British victory. Instead, the Battle of Long Island was the first major blow of a war that would drag on for seven more years and end in a recognized American democracy. “The Battle for New York: the City at the Heart of the American Revolution.” The Battle for New York: the City at the Heart of the American Revolution, by Barnet Schecter, Jonathan Cape, 2003, p. 3. “The Battle of Brooklyn 1776.” The Battle of Brooklyn 1776, by John J. Gallagher, Heritage Books, 2004, pp. xv-50. “Battle of Long Island.” Essential New York City Guide, www.essential-new-york-city-guide.com/battle-of-long-island.html. This article was published in the August 11th, 1938 edition of Ken magazine. It was, until recently, available online. Efforts to find the copyright holder were unsuccessful and it is, therefore, considered an abandoned work.

It is copied here because it provides insight into the limited and unfair job prospects African Americans faced in the earliest part of the twentieth century as students read the book Bud, Not Buddy. |

Author

I often struggle to find websites with thorough explanations in simple language to help kids understand historical events or scientific concepts, so I decided to create some of my own! -Cookie Davis

Archives

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed