|

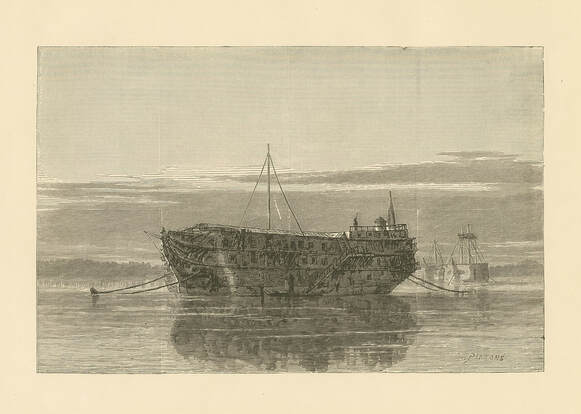

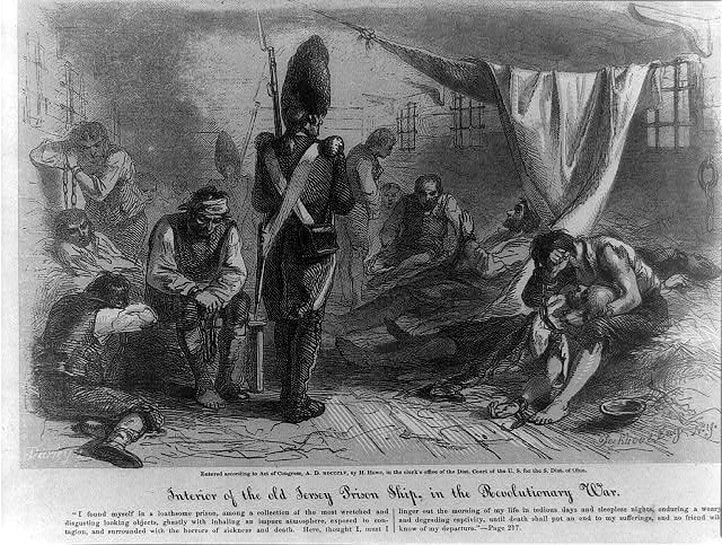

This is an excerpt from an article originally appeared on the website easyrivernyc.org that is no longer published. Images have been added to increase visual appeal and text simplified for students. More Americans died in British prison ships in New York Harbor than in all the battles of the Revolutionary War. There were at least 16 of these floating prisons anchored in Wallabout Bay on the East River for most of the war, and they were known for their filth, pests, infectious disease and horror. The ships were all wretched, but the most notorious was the Jersey. Following the Battle of Long Island in August, 1776, and the fall of New York City soon after, the British found thousands of prisoners on their hands, and the available prisons in New York filled up quickly. Then, as the British began seizing hundreds of seamen off privateers, they turned a series of aging vessels into prison ships. There were more than a thousand men at a time packed onto the Jersey. They died with such regularity that when their British jailers opened the hatches in the morning, their first greeting to the men below was: "Rebels, turn out your dead!" There were 4,435 battle deaths during the Revolutionary War, according to the Department of Defense. One historian estimated that there were between 7,000 and 8,000 prison ship deaths, but other sources claim even more. A letter-writer from Fishkill in 1783 claimed that on the Jersey alone, 11,644 died. Although that figure is unlikely for the one ship, it is reasonable for all the prison ships together, and is cited regularly. Built in 1735 as a 64-gun ship, the Jersey was was converted to a prison ship in the winter of 1779-1780. Virtually stripped except for a flagstaff and a derrick for taking in supplies, the Jersey was floated, rudderless, in Wallabout Bay, about 100 yards offshore of what is now the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Its portholes were closed and replaced by a series of small holes, 20 inches square, crossed by two bars of iron. There were various ways to get off the prison ships. The British had a standing offer that any prisoner could be released immediately if he joined the British forces, and an unidentified number did so. Prisoners who carried money with them could buy their way off the ship. Others managed to escape. Also, prisoner exchanges were quite common, with officers exchanged for officers, seamen for seamen, soldiers for soldiers. But for vast numbers of prisoners, there were only two possibilities: death or the end of the war, whichever came first. At war's end, survivors were released, and the prison ships abandoned. In later years, bleached bones of the dead were constantly exposed to the tides and weather along the Long Island shore. And well into the next century, low tide regularly exposed the rotting timbers of the Jersey, the ship they called Hell. Bookhout, Edward. “Interior HMS Jersey.” Wikimedia Commons, Wikimedia Foundation, 12 Nov. 2012, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki

/File:Interior_HMS_Jersey_1855.jpg. Daugherty, Greg. “The Appalling Way the British Tried to Recruit Americans Away from Revolt.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 31 Jan. 2020, www.history.com/news/british-prison-ships-american-revolution-hms-jersey. History.com Editors. “The HMS Jersey.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 19 Mar. 2010, www.history.com/topics/american-revolution/the-hms-jersey. “History: Tragedy: Prison Ships & General Slocum.” East River NYC, 2008, www.eastrivernyc.org/content/history/tragedy/index.html. “Prison Ship Jersey.” Wikimedia Commons, New York Public Library, 13 May 2016, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki /File:Prison_ship_Jersey_(NYPL_b13512824-420924).jpg. Comments are closed.

|

Author

I often struggle to find websites with thorough explanations in simple language to help kids understand historical events or scientific concepts, so I decided to create some of my own! -Cookie Davis

Archives

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed